The death of Hugh Hefner at age 91 hurled us headlong back into recollections of the 1960s and what Playboy was supposed to be about.

If you weren’t a Playboy reader in those days—and few of us alive today were, let’s face it, since that would imply you were then a male between 25 and 50 years of age, making you about 90 years old today—you had a weird notion of it, one that came filtered through the schoolyard and MAD magazine. Playboy was a dirty magazine, a skin book. It had pictures of “naked ladies.”

Nobody said “porn.” Porn did not exist, at least in the general consciousness. Porn was something you might discover when you grew up and got perverted and hung out in back alleys, the same way you might end up a junkie. Whatever that is. These were things way off the edge of the known world.

What you did know—what everyone knew—was that there was such a thing as a dirty magazine with pictures of “naked ladies,” and the one that everyone knew about was Playboy.

Sophisticated adolescents might become aware that Playboy was really an elegant magazine, with a high level of literary content. Borges and Bradbury and Graham Greene and Kingsley Amis. Sort of what The New Yorker might have been if it had more money, and wasn’t edited by the spergy William Shawn. And wasn’t chockfull of experimental fiction by Donald Barthelme, and John McPhee treatises on the history of yeast. And maybe had a fold-out “naked lady” picture stapled in the middle.

Few magazines pervaded the public consciousness the way Playboy did. Henry Luce’s Life was at least as iconic in its heyday, surely. But nearly everyone had first-hand knowledge of Life, whereas Playboy was something known mainly by reputation and pop-culture allusion.

In the script for The Apartment (1959), there is a scene where the Jack Lemmon character thumbs through the latest issue in bed, stopping to peruse a feature on hats for the young executive. Although this scene was cut from the final film, Lemmon shortly turns up wearing a bowler, and explains to Shirley MacLaine that he’d just seen it in a magazine article.

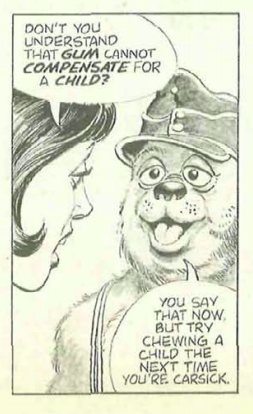

MAD magazine referred to Playboy in nearly every issue. In 1964 it instituted a sort of parody of Playboy’s most notorious feature, and gave us the long-running “Mad Fold-In,” an Al Jaffee cartoon that revealed a hidden image when you creased the back cover.

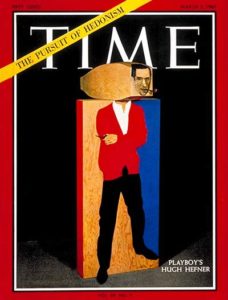

Playboy was literary, arty, trendy. When Time magazine did its cover on Hugh Hefner in early 1967, it appropriately used a pop-art wood sculpture of Hef by Marisol Escobar. This “Marisol” is now pretty much forgotten now, but she was a hot item then.

People who are now middle-aged and beyond are well aware of this glossy aspect of Playboy. It pushed a kind of sportscar-and-cloth-cap sophistication, took top dollar for its ads, and paid all its contributors well.

Playboy was class—a showy, crass, upwardly mobile kind of class, the kind of class displayed by people who put name-brand university decals on the back windows of their station wagons—but it was still was a sort of class, one that the rank-and-file could perceive and aspire to.

For people under 35, this notion of Playboy has pretty much evaporated. The porn culture of the Internet undercut Playboy‘s edgy appeal. Airbrushed centerfolds of “naked ladies” were now nostalgia stuff, like old Bettie Page pictures. At the same time, people stopped buying print magazines, and reading literary fiction.

So here we have a generational disjuncture in our perception of Hugh Hefner and Playboy. The old folks put him in a category with William S. Burroughs and Norman Mailer—an iconic, mold-breaking trend-setter.

But to the kids, Burroughs was just a junkie, and Mailer a thuggish drunk. While Hefner was a porn tycoon who published pictures of “naked ladies.”

Author: “Uncle Bill” Cobbett

Old as dirt and twice as jolly.